Strategic opportunities under the ASU 2017-12 hedge accounting standard

Summary

The ASU 2017-12 hedge accounting guidance expands the strategies that qualify for hedge accounting and introduces opportunities for companies to mitigate earnings volatility.

Key takeaways

- FASB guidance (ASU 2017-12) removes barriers under legacy standards (ASC 815) that disallowed some common hedging strategies from qualifying for hedge accounting, creating new opportunities for companies to mitigate earnings volatility.

- This creates four categories of opportunities for companies to mitigate earnings volatility: excluded components, fair-value hedges of FX risk, contractually specified risks, and intentional over-hedging.

- Because the ASU 2017-12 hedge accounting standard enables organizations to expand their hedging programs, supporting the hedge accounting process with a robust exposure management tool becomes more critical.

(Updated 1-11-24)

Many U.S. companies adopted the FASB hedge accounting guidance (ASU 2017-12) and saw firsthand that their financial reporting results now better align with the economic objectives of certain financial risk management activities. The guidance removes barriers under legacy standards (ASC 815) that disallowed some common hedging strategies from qualifying for hedge accounting, creating new opportunities for companies to mitigate earnings volatility. For these reasons, Chatham has seen the standard championed by both treasury and accounting teams.

Below, Chatham provides insight into four categories of strategic opportunities: excluded components, fair-value hedges of FX risk, contractually specified risks, and intentional over-hedging.

Excluded components

Under ASU 2017-12, organizations can reduce some of the administrative burden associated with effectiveness assessments and enable more predictable P&L reporting by recognizing amounts excluded from hedging relationships on a “systematic and rational” basis, which is typically interpreted in practice as straight-line amortization. Under legacy GAAP, excluded components were required to be marked-to-market, often causing significant income statement volatility. Companies who experience timing uncertainty around forecasted transactions or those with certain basis mismatches can now apply the spot method, recognizing the excluded component over the life of the hedging relationship while eliminating the need to model certain mismatches. The FASB also extended the systematic and rational concept to net investment hedges when the spot method approach is utilized. This change permits companies to achieve more favorable financial reporting results for certain hedging instruments, such as cross-currency swaps. The examples below demonstrate the benefits seen in a handful of common hedging strategies:

Example 1: FX forward designated as a cash-flow hedge

Example 1 represents a foreign currency forward in which the hedger would like to exclude the forward points embedded in a forward contract from the hedging relationship. This is commonly referred to as the “spot method” because only changes in fair value related to spot rates are deemed to be included in the hedging relationship. This contrasts with the “forward method” where all changes in fair value (both spot and forward components) are included in the hedging relationship and thus are required to be incorporated into effectiveness testing.

FX forward designated as a cash-flow hedge

Assume that ABC Company is a U.S. entity and is entirely U.S. dollar (USD) functional. ABC expects to earn one million Euros of revenue from a sale to occur exactly one year in the future and expects to collect the foreign proceeds on the day of the sale. To hedge the forecasted foreign revenue, they sell one million Euros (EUR) forward a year. When ABC’s treasury team goes out to the market to execute a forward contract, they note that the EUR-USD spot rate is 1.10. However, the forward contract they are able to execute is based on a forward rate, which represents the spot rate plus forward points (which are dependent upon market dynamics, including supply and demand, and interest rate differentials).

In ABC’s case, the forward points are 0.03, bringing the EUR-USD forward rate to 1.13. The company’s forecasted foreign revenue is exposed to the changes in the spot rate, which is 1.10 today. However, the gain or loss that ABC will realize in a year on the derivative contract will be based on the difference between spot at the time of settlement and the hedged rate of 1.13. Said differently, the 0.03 of forward points exist in the derivative but not in the underlying exposure.

Addressing timing differentials

Timing differentials are a significant factor when employing the forward method. If ABC’s forecasted timing for the transaction changes to 13 months in the future, they are required to model the difference. That modeling is complex, it introduces a mismatch into the effectiveness assessment, and is often administratively burdensome. Conversely, with a spot approach, the company can exclude forward points from the effectiveness assessment used to qualify for hedge accounting. Under the spot method, the organization is only required to compare the spot changes on its derivative contract to the spot changes on the underlying exposure, and these are going to align to the extent that the notional of the derivative matches the number of Euros being hedged. Unless ABC experiences a shortfall in the number of Euros they expect to earn in a year (e.g, the forecasted transaction), using the spot approach to account for the transaction will likely result in less administrative burden over the life of the hedging relationship.

Example 2: Net investment hedge

Chatham has seen quite a bit of excitement from organizations seeking to apply the “systematic and rational" treatment of excluded components for trades designated as net investment hedges under the spot method. In fact, this approach has prompted more of our clients to early adopt the ASU 2017-12 standard than any other. In this example, a U.S. firm has a Euro functional subsidiary that generates €1M of net income and cash flow each quarter. As in the previous example, the subsidiary’s net income is worth more U.S. Dollars as the Euro appreciates and less as it depreciates. To mitigate this risk, many companies will take out Euro debt with the objective of aligning Euro income and expenses to create a natural hedge.

Taking advantage of interest rate differentials

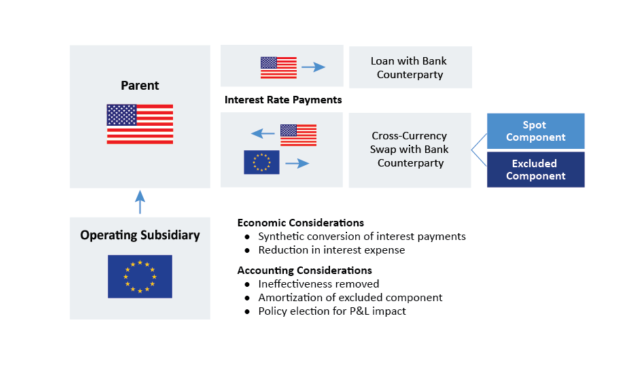

Interest rate differentials between the U.S. and Europe make issuing Euro debt enticing for many companies. However, issuing debt abroad can be challenging as this may require the transaction to be underwritten abroad, there are often regulatory issues, and foreign investors often want debt covenants that may differ from those required by U.S. investors. For these reasons and others, organizations often choose to synthetically convert their U.S. Dollar debt into Euro debt to take advantage of interest rate differentials. This can be accomplished by executing a cross-currency swap.

Companies execute cross-currency swaps to take advantage of interest rate differentials

Assume, for example, that a company has a fixed-rate term loan that requires quarterly 6% U.S. Dollar interest payments, but the company is able to execute a cross-currency swap that allows them to pay a 5% Euro coupon and receive a 6% U.S. Dollar coupon each quarter. By executing this cross-currency swap, the company achieved their economic objective of converting U.S. Dollar debt to Euro debt and even received the benefit of a lower effective interest rate. Under legacy GAAP, most companies would designate this derivative as a net investment hedge, resulting in all changes in fair value being recorded to CTA, while the 6% coupon on the dollar loan continues to be recorded as interest expense. The company was unable to see the net effect of a 5% Euro interest expense in their income statement, even though this was the economic reality they had achieved by executing the hedge. Under the revised guidance, this company could designate the cross-currency swap as a net investment hedge utilizing the spot method, and would receive the benefit of reclassifying payments and accruals as a reduction to interest expense each period.

Updated accounting guidance for cross-currency swaps

The example below illustrates these benefits by comparing the financial statement impact of a cross-currency swap designated under legacy ASC 815 forward method vs. the strategy described above. In both cases, the company has executed a cross-currency swap to synthetically convert U.S. Dollar debt to Euro debt, which has economically reduced their interest expense from $150 per year to the U.S. Dollar equivalent of $125 (through a lower Euro coupon, expressed in consolidated U.S. Dollars).

Note that the spot method was permissible pre-ASU-2017-12. However, practitioners didn’t have the benefit of recognizing excluded components using a “systematic and rational basis." Consequently, most net investment hedges were historically designated under the forward method. The firm on the left has designated their trade using the forward method under legacy guidance to avoid the mark-to-market volatility associated with excluded components. The hedge was deemed to be perfectly effective, and thus all changes in the fair value are recorded to CTA and nothing will hit the income statement until the net investment is “substantially liquidated.” As a result, no currency fluctuations are represented on the income statement, which shows a financial impact of $150 in interest expense each year even though, economically, the firm has reduced its interest payments. While this treatment removes volatility from the income statement, it also eliminates any P&L benefit of swapping interest rate payments to a lower rate environment by deferring those changes in value in CTA.

In contrast, the firm on the right designated the same hedge using the spot method under the ASU 2017-12 guidance. Changes in spot value are deferred to CTA while all other components are excluded from the hedging relationship and reclassified to earnings as they are realized through accruals and coupon payments. This demonstrates the benefit of the ASU 2017-12 guidance because the company can amortize those excluded components over the life of the hedge, delivering an even and predictable P&L recognition pattern. This eliminates the volatility caused by applying this method under the old standard while also representing the economic benefits of the cross-currency swap on the income statement.

How the ASU 2017-12 accounting guidance minimizes volatility on the balance sheet for cross-currency swaps

While there are clear benefits to utilizing this strategy, there are also nuances and transition considerations that should be carefully weighed before implementing a spot method program. Additionally, while legacy ASC 815 provided flexibility regarding the line item companies can use to recognize excluded component gains and losses, the FASB now requires changes in the value of excluded derivative gains and losses to be applied to the same financial statement line item as the included components. For many companies, this change has made a spot designation significantly less desirable than it had been under legacy GAAP.

Fair value hedge of foreign exchange risk

In addition to the excluded component strategies above, ASU 2017-12 extends the application of the excluded component model for fair value hedging relationships, which may spark interest from those looking to hedge foreign currency denominated interest-bearing assets and liabilities. As in other areas, the ability to recognize the inception value of excluded components in a systematic and rational manner shields the P&L from the mark-to-market impact of those excluded components and other mismatches that would be felt under the legacy standard fair value model.

For example, let’s say an entity wants to hedge the fair value of foreign currency risk associated with a Euro-denominated fixed rate note and wishes to do so with fixed-fixed cross currency swap. When designating a cross currency swap as a fair value hedge of FX risk associated with foreign denominated debt, the changes in fair value of the derivative and the hedged item will not perfectly offset. This is the case even if all economic terms are matched between the hedging instrument and the hedged item. To remedy this, an entity can elect to exclude the total forward to spot difference from the assessment of hedge effectiveness and recognize those excluded components in earnings. This results in a more aligned hedging relationship in which changes in spot on the hedging instrument impact the P&L in the same line item as the ASC 830 remeasurement on the recognized foreign currency denominated asset or liability. The excluded components are recognized in the same line item in which the impact of the hedged item is recorded. Any subsequent changes in the inception excluded components are recorded in OCI, which would include any changes in counterparty credit risk as modeled by an ASC 820 compliant credit valuation adjustment.

The result is a financial statement impact similar to the application of cash flow hedge accounting without the need to assert probability over the hedging relationship. This gives end users looking to hedge foreign-currency-denominated interest-bearing assets and liabilities another avenue to achieve similar financial statement results if circumstances exist that may preclude other types of hedge accounting.

Contractually specified risks

Prior to ASU 2017-12, ASC 815 allowed companies to isolate certain risk components in cash-flow hedges of financial items. For example, if a company had 3-month LIBOR debt and executed a pay fixed, receive 3-month LIBOR swap to effectively fix their all-in interest expense, the organization would look specifically to the LIBOR (benchmark) component of that contract without the need to consider the spread over LIBOR in the assessment of effectiveness. This made hedging cash flows from financial items such as interest-rate risk much less complex and onerous than hedges of non-financial items.

Non-financial exposures, such as commodities, were treated differently. For example, assume a company plans to buy 100 tons of aluminum in six months, and each of their vendors price aluminum at the LME monthly average price, plus freight and fabrication costs. If that hedger executed an over-the-counter forward contract to buy aluminum six months forward at the LME monthly average price (i.e. no economic mismatch), the entity would be required to demonstrate that their hedge was highly effective by comparing the derivative to an exposure that captured all variability in cash flows attributable to the hedged transactions, including freight and fabrication charges. Capturing estimated freight and fabrication charges creates administrative burden, particularly for procurement teams that work with multiple vendors. Furthermore, changes in estimated freight and fabrication costs could cause the entity to record hedge ineffectiveness to the income statement and possibly cause the hedge to fail to qualify for hedge accounting.

ASU 2017-12 permits entities to focus on a contractually specified component. In the example above, if the LME aluminum price meets the requirements to be deemed contractually specified, changes in freight and fabrication costs would no longer be relevant. We see this as a huge win for hedgers of commodity risk but caution that we have seen some practitioners encounter challenges while implementing this simplified approach.

Challenges with old approach

- Difficulty in quantitatively demonstrating that exposures shared the same risk

- Basis differences like shipping and manufacturing costs, which couldn’t be excluded, could sometimes lead to failing effectiveness tests

- Even when trades qualified, there was still the possibility for material amounts of ineffectiveness

- Monitoring and quantifying the basis difference between hedges and exposures was particularly burdensome for commodity hedgers who faced compressed margins

Benefits of the new approach

- Requirement to perform a same risk analysis is eliminated if all purchases share the same contractually-specified risk

- Easier to qualify for hedge accounting by eliminating basis risk from the hedging relationship

- Better accounting results as the requirement to separately measure and record ineffectiveness has been eliminated

NOTE: Chatham has seen companies struggle with unintended consequences when adopting this approach. Under ASU 2017-12, it is important to determine whether the contract(s) containing the contractually-specified risk meet the definition of a derivative and if there is a requirement to designate the contract for the “normal purchase, normal sale” scope exception in order to take advantage of this new strategy. In the FASB’s recently released exposure draft, this language was amended and, therefore, changes may occur once the final update is released in 2020. Chatham recommends discussing this approach with an advisory partner with expertise on this issue.

Intentional over-hedging

Intentional over-hedging is a strategy that can be applied when a treasury or procurement team wishes to execute a derivative with a specific notional to mitigate an economic risk, however, the company doesn’t have sufficient hedge accounting capacity to designate the entire transaction in a hedge accounting relationship.

For example, assume that an organization plans to sell a foreign entity and wishes to execute an FX forward contract to sell 1B foreign currency units (FCUs) forward to hedge the U.S. Dollar equivalent of the foreign proceeds they expect to receive. The accounting team determines that this hedge should be designated as a net investment hedge. However, due to certain accounting constraints, they are only able to find 900M FCUs of net investment hedging capacity to designate the hedge against.

Prior to ASU 2017-12, designating a forward contract to sell 1B FCUs against a net investment of 900M FCUs would result in 10% of the hedges change in fair value flowing through earnings each period in the form of hedge ineffectiveness. Therefore, intentionally over-hedging didn’t make sense under the previous guidance. Consequently, this entity would have been forced to choose between letting accounting constraints dictate economic decisions (i.e. execute a hedge to sell 900M FCUs), and hedging 100% of their economic exposure knowing they will be forced to live with a less than ideal accounting result. Under the ASU 2017-12 guidance, the requirement to separately record hedge ineffectiveness goes away and, in an ASU 2017-12 world, the entity can now designate the 1B FCU forward as a hedge of its 900M FCU net investment in a foreign subsidiary. As long as the hedge remains highly effective, all changes in fair value of the derivative would be recorded to CTA until complete or substantial liquidation of the foreign subsidiary (assuming the entity did not exclude any components from the relationship).

Strategic considerations

As companies continue to incorporate the ASU 2017-12 FASB hedge accounting guidance into their accounting treatments, treasury and accounting teams can gain significant advantages by understanding the strategic opportunities and streamlined workflows presented by these changes. Working with their auditors and strategic advisors, organizations can initiate new hedging programs, mitigate more volatility and better meet their financial objectives. Time spent evaluating these opportunities and integrating technology to implement them can positively impact the organization for years to come.

Technology considerations

Because the ASU 2017-12 hedge accounting standard enables organizations to expand their hedging programs, supporting the hedge accounting process with a robust exposure management tool becomes more critical. Insight into your overall treasury risk management can provide direction on how to most effectively expand your hedging program. From both a technology and advisory perspective, ChathamDirect delivers the capabilities to support opportunities introduced by the ASU-2017-12 hedge accounting guidance.

Raising the bar on hedge accounting

With the right tools and expertise, many organizations have found hedge accounting to be not only attainable but also essential, as market volatility continues to impact financial performance. As the trusted hedge accounting advisory and technology partner for accounting clients across the globe, Chatham is well-equipped to help companies of all sizes and industries grow their hedge accounting programs to protect financial results and stay competitive in an increasingly complex and challenging business environment. The next year will bring many opportunities for hedge accounting professionals to deliver value to their organizations. Within this shifting landscape, accessing the information, expertise, and technology to execute a successful hedge accounting program has never been more critical. Contact Chatham if you would like to speak with an expert about your hedge accounting strategy.

Talk to an expert

Schedule a call to discuss how your organization can take advantage of opportunities under the ASU 2017-12 hedge accounting standard.

Disclaimers

Chatham Hedging Advisors, LLC (CHA) is a subsidiary of Chatham Financial Corp. and provides hedge advisory, accounting and execution services related to swap transactions in the United States. CHA is registered with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) as a commodity trading advisor and is a member of the National Futures Association (NFA); however, neither the CFTC nor the NFA have passed upon the merits of participating in any advisory services offered by CHA. For further information, please visit chathamfinancial.com/legal-notices.

Transactions in over-the-counter derivatives (or “swaps”) have significant risks, including, but not limited to, substantial risk of loss. You should consult your own business, legal, tax and accounting advisers with respect to proposed swap transaction and you should refrain from entering into any swap transaction unless you have fully understood the terms and risks of the transaction, including the extent of your potential risk of loss. This material has been prepared by a sales or trading employee or agent of Chatham Hedging Advisors and could be deemed a solicitation for entering into a derivatives transaction. This material is not a research report prepared by Chatham Hedging Advisors. If you are not an experienced user of the derivatives markets, capable of making independent trading decisions, then you should not rely solely on this communication in making trading decisions. All rights reserved.

19-0070